Eta Aquarid meteor shower 2024: Where, when and how to see it

The Eta Aquarids could put on quite the show in 2024!

The Eta Aquarid meteor shower 2024 is active between April 15 and May 27 and peaks on the night of May 4 and predawn hours of May 5.

The peak of the Eta Aquarids is around the time of the new moon, therefore moonlight will provide minimal interference to meteor hunters, unlike the fully illuminated moon in 2023.

The chunks of space debris that create the Eta Aquarids come from a celestial icon: Halley's Comet. The Eta Aquarid meteor shower is categorized as a strong shower; it is best viewed from the Southern Hemisphere or close to the equator, although folks in some northern latitudes can also observe them.

Related: Meteor shower guide: Where, when and how to see them

If you're looking for a good camera for meteor showers and astrophotography, our top pick is the Nikon D850.

The maximum rate for shooting stars in a clear sky will be about 50 per hour, according to the American Meteor Society (AMS). These fast meteors travel across the sky at about 41 miles (66 kilometers) per second.

Where can you see the Eta Aquarid meteor shower?

Meteor showers are named after the constellation from which the meteors appear to originate. From Earth's perspective, the Eta Aquarids appear to come from approximately the constellation Aquarius.

Right ascension: 23 hours

Declination: -15 degrees

Latitudes: Between 65 and -90 degrees

You can see the Eta Aquarids best in the Southern Hemisphere, where they are one of the most prolific showers of the year. They can also be viewed north of the equator where observers can expect to see around 10 to 30 meteors per hour during the shower's peak. All you need to catch the show is darkness, somewhere comfortable to watch and a bit of patience.

Though the Eta Aquarids' radiant is the Aquarius constellation, it is not the source of the meteors. Don't look directly at Aquarius to see the meteors, as they will be visible across the night sky. Make sure to move your gaze around to nearby constellations as meteors closer to the radiant have shorter trains and are more difficult to spot. If you only look at Aquarius, you might miss the more spectacular Eta Aquarids.

How can you see the Eta Aquarid meteor shower?

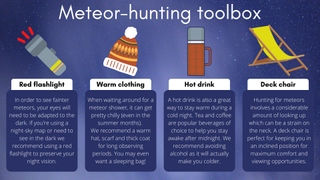

For the best view of the Eta Aquarid meteor shower, go to the darkest possible location, lean back and relax. You don't need any special pieces of equipment like telescopes or binoculars as the secret is to take in as much sky as possible and allow at least 30 minutes for your eyes to adjust to the dark. Avoid using your phone and make sure you have a red light setting on flashlights to preserve your night vision.

If you want more advice on how to photograph the Eta Aquarids check out our how to photograph meteors and meteor showers guide and if you need imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Best time to view the Eta Aquarids

To see the Eta Aquarids, Bill Cooke, the lead for the Meteoroid Environment Office at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, recommends getting outside at 2:00 a.m. local time. From then on, the rates will continue to increase until dawn.

"The Etas are not a shower that you can go out to see after sunset because the radiant won't be up," Cooke wrote.

To calculate sunrise and moonrise times in your location check out this custom sunrise-sunset calculator.

What causes the Eta Aquarid meteor shower?

Similar to October's Orionid meteor shower, the Eta Aquarid meteor shower is caused by ice and dust left behind by a celestial icon: Halley's Comet.

When Earth passes through the comet's debris, the "comet crumbs" heat up as they enter Earth's atmosphere, producing impressive "shooting stars" that streak across the sky.

Halley's Comet takes about 76 years to orbit the sun once and will not enter the solar system again until 2061.

The comet is named after English astronomer Edmond Halley, who examined reports of comets approaching Earth in 1531, 1607 and 1682. He concluded that these sightings were all of the same comet returning over and over again. Halley predicted the comet would return in 1758. Though he did not live to see the comet's correctly-predicted return, it was later named in his honor.

Additional resources

Have you seen a fireball recently? Report the sighting to the American Meteor Society to help contribute to fireball research. Explore the historical significance of Halley's Comet and the Battle of Hastings with this NASA feature. Take a tour of meteors and meteorites through history on this Google Arts & Culture feature courtesy of Adler Planetarium.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing Eta Aquarid meteor shower photo that you'd like to share with us and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, send images and comments to us at spacephotos@space.com.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!